Articles on the Great Books as an Essential Element of Classical Education

“We are tied down, all our days and for the greater part of our days, to the commonplace. That is where contact with the great thinkers, great literature helps. In their company we are still in the ordinary world, but it is the ordinary world transfigured and seen through the eyes of wisdom and genius. And some of their genius becomes ours. . .”

– Mortimer J. Adler

“I am convinced that classical education holds out the greatest hope for our children’s future flourishing and for renewal of Church life.”

– Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone

Please click on any of the articles below for more information on the Great Books as an essential requirement for authentic Classical Education. They are the “textbooks.”

From one of our first students…If it’s anybody’s fault that I’m doing this crazy PhD thing now, it’s you – Great Books opened the lid of my world and set me on fire. I’m forever grateful for the program and the education I received from it; it is one of the greatest gifts I have ever received, and one that continually bears fruit and enriches my life in new and beautiful ways. I can never repay you for believing that 15-year-olds are capable of reading as much as graduate students! In a way my serious relationship to the Western canon began 15 years ago, in your classroom. This led to my place now, as a sort of professional bookworm. My life as it stands is pretty great, and I owe a lot of where I am now to you. Thank you so much for teaching. Pax, Kelsey B.

The Best Age to Begin the Study of the Great Books

by Patrick S.J. Carmack

Anytime available for leisure is a good time to begin or resume the study of great books. However, for young people who have never studied them, two limitations frame the answer to the question: when is the ideal time to begin the study of the Great Books? The first is a limitation intrinsic to the student, the second extrinsic:

1.) The student must be able to read reasonably well, and ideally should also be able to write, speak and listen well. In other words, a Great Books student should have completed the study of the trivium–the elemental liberal arts–and so know how to read, write, speak and listen well. I would add to those arts the ability to use a personal computer to locate and read the various texts and commentaries and to write and submit essays online. Given that these learning arts are typically taught in the elementary grades (1st-8th), the study of the Great Books logically should follow sometime after completion of 8th grade—primary education.

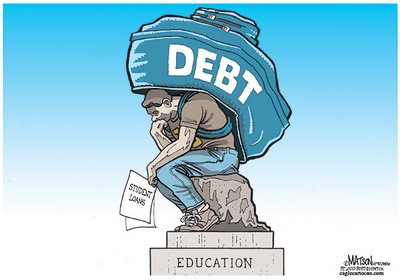

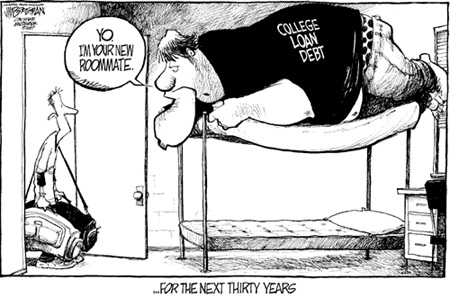

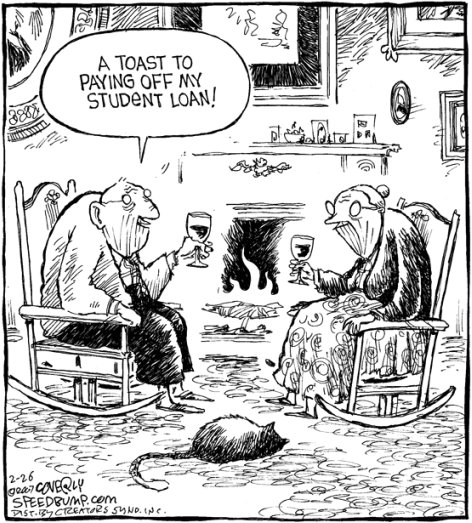

2.) The other limit is imposed by factors extrinsic to the student: the responsibilities and financial pressures of rising college costs, housing, student loan debt, costly auto and health insurance, marriage and parenthood, effectively end the availability of sufficient leisure time and financial resources necessary for formal, liberal educational opportunities for most college-age students. By that age students are under increasing pressure to complete some specialized, vocational or professional education in order to generate an income to fulfill those responsibilities and limit their debts.

The conclusion is that—ideally—Great Books education should begin after the first eight years of primary education, during the whole of secondary education—the four high school years. For most students this means beginning the study of the Great Books in 9th grade (14 year olds) or after, and continuing at least through 12th grade (18 year olds or so).

In the United States the high school years at schools are too often an intellectual wasteland, as most high school graduates would readily attest, which needlessly protract study of the trivium which has been expanded into secondary education due to our remarkably ineffective public (and most private) elementary school education. This is supplemented with thin-to-bad literature selections (such as much of that proposed by Common Core), with much time wasted on dubious social engineering materials and insipid textbooks designed by large publishing houses for the “average” student. Dr. Adler:

“As far as the United States is concerned, the reorganization of the educational system would make it possible for the system to make its contribution to the liberal education of the young by the time they reached the age of eighteen…The tremendous waste of time in the American educational system must result in part from the fact that there is so much time to waste.”

Many years ago–from the Middle Ages to the last century–the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree signified completion of the secondary level of education (following the elementary, grammar or primary level) and so readiness to enter into the third level of formal education – the university, for specialization in one’s chosen field. With that background in mind Dr. Adler wrote:

“If I had any hope that in the foreseeable future, the educational system of this country could be so radically transformed that the basic liberal training would be adequately accomplished in the secondary

[i.e., high] schools and that the Bachelor of Arts degree would then be awarded at the termination of such schooling, I would gladly recommend that the college be relieved of any further responsibility for training in the liberal arts…if we are going to have general human schooling in this country, it has to be accomplished in the first twelve years of compulsory schooling…it would be appropriate to award a Bachelor of Arts degree at the completion of such basic schooling. Doing so would return that degree to its original educational significance as certifying competence in the liberal arts, which are the arts or skills of learning in all fields of subject matter.”

Renowned Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain held virtually the identical view as Dr. Adler: “I advance the opinion, incidentally, that, in the general educational scheme, it would be advantageous to hurry the four years of college, so that the period of undergraduate studies would extend from sixteen to nineteen. The B.A. would be awarded at the end of the college years [thus at 19 years of age], as crowning the humanities…” Their view of completing generalist, liberal education by age 18-19 is nothing new in this country.

In colonial America, before entering school at the age of fourteen or fifteen, students were expected to be able to speak Latin, and in college they were fined for not speaking in Latin, except during recreation. Latin was the language of most of their textbooks and lectures. Knowledge of New Testament Greek was required for admission, and students also studied Homer and Longinus in Greek. In Latin the chief authors were Cicero, Virgil, and Horace. A lifelong interest in the classics was common. “Every accomplished gentleman,” says Wertenbaker, “was supposed to know his Homer and his Ovid, and in conversation was put to shame if he failed to recognize a quotation from either.” Self-made men, like Benjamin Franklin, without the benefit of college, derived more from the ancient world than one would expect, but the more typical Founding Fathers meditated long and deeply on the ancient patterns of democracy and republics, and Jefferson was only expressing a frequent view of his time when he said of ancient literature: “The Greeks and Romans have left us the present models which exist of fine composition whether we examine them as works of reason, or style, or fancy… To read the Latin and Greek authors in the original is a sublime luxury.” The history, philosophy, and literature of the ancients did not seem remote or antiquated, but intimately present because permanently enlightening.

In the Harvard Classics, Harvard President Dr. Charles Eliot prepared a selection of 60 readings from that great books set to provide a “pleasant introduction” to it for students ranging in age from 12 to 18, and stated “There is no place where the Harvard Classics find greater usefulness than to children [referring to the same 12-18 year old readers]. If you have children in your family… let them have free access to the Harvard Classics [which] will bring to the growing boy and girl a familiarity with the supreme literature, at the impressionable age when cultural habits are formed for a lifetime.”

Scientific research strongly supports Dr. Eliot’s opinion. In a study published in the Journal of Philosophy in Schools (2015) several faculty members from Sam Houston State University in Texas decided to replicate a 2007 study conducted in Scotland on the effects of a philosophy for children program. Philosophical works are a large component of Great Books courses. The original study was one of few randomized, controlled clinical trials assessing the impact of a philosophy for children program. It showed significant gains in cognitive abilities by children who participated in weekly philosophical group discussions.

This new study found that the seventh-grade students who had experienced the philosophy for children program showed significant gains relative to those in the seventh-grade control group, providing evidence for the main contentions of the original 2007 study — namely, that “regular, one hour per week, structured community of inquiry philosophy for children sessions are a relatively powerful educational intervention which boosts students’ cognitive abilities significantly while doing so at a very small cost both in materials needed and in instructional time.”

Another study by Durham University in the United Kingdom further strengthens the case for philosophy for children and provides evidence for its efficacy as an intervention in closing the achievement gap. This study, which included more than 3,000 students in 48 public primary schools across England evaluated January-December, 2013, found that “pupils’ ability in reading and math scores improved by an average of two months over a year,” but, more importantly, that the “disadvantaged pupils in the trial, those on free school meals, saw their reading skills improve by four months, their math by three months and their writing ability by two months.”

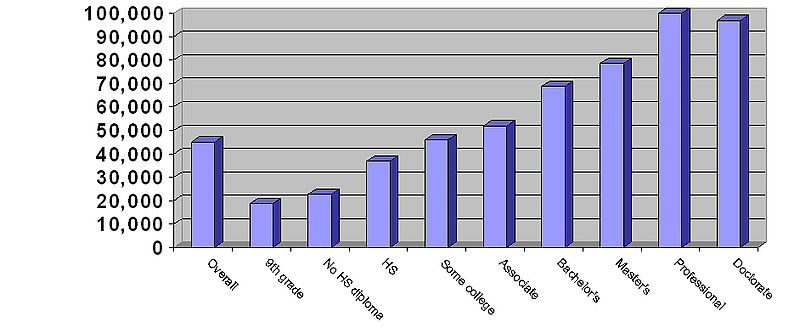

Nobel Prize-winning University of Chicago economist Gary Becker made much the same point about the importance of early education when he noted the effect of the lack thereof in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution in the United States, in which too many children are neither learning the skills nor adopting the habits and values that other children acquire. One result is increasing income inequality. For example, prior to 1950, college graduates earned about 40 percent more than high school graduates, on the average. Today they earn 80 percent more.[i] Thus education prior to college admittance age (roughly age 18) is increasingly important in our society. When is it too late to make up for deficient early education? Becker says studies show that government job-training programs for 16-year-olds do not succeed because they cannot overcome the failure to learn skills in their first 16 years.

Can government schools solve the problem by providing early education and skills that traditionally have been provided by parents? Becker, citing various studies, concludes there is no evidence government schools can solve the problem. What about replacing real mothers with professional day care personnel? Sweden tried that on a grand scale—a literal, Spartan-like nationalization of the family—at great social cost, but found no evidence of positive effects on children. By contrast, early home education in the liberal arts, complimented at the secondary level with general liberal education in the humanities such as is contained in the great classics, offers a well-tested, traditional solution to the current educational crisis. As schools in general do not offer such an education at the secondary level (which has been increasingly “dumbed down” in Gatto’s phrase), it is left for parents and educators to find alternative ways to provide this for their students.

James Heckman, Nobel Laureate, 2000 Researched the Lifecycle Dynamics of Skill Formation

Studies by another Nobel-Prize winning (2000) economist at the University of Chicago, James Heckman, found that “enriched environments” of learning enhanced IQ: “But that’s because when a kid is in a program, he’s being enriched and being enhanced… there is a [IQ] fade out that occurs when people get out of these enriched environments… We’re so used to thinking of IQ as being genetically given, used to thinking of these traits as somehow embedded at birth, but they’re not. The whole literature in genetics is now talking about gene-environment interactions: epigenetics.” Public schools, and most private ones, too often provide impoverished learning environments using inferior texts, as if the learning environment did not matter – Heckman’s studies show it does.

Heckman wrote: “When you raise Rhesus monkeys (they share about 95 percent of humans’ genes) with a form of disadvantage, you affect 23 percent of all their genes. The genes are there, but the genes themselves don’t do anything. So you can have two identical monkeys, one raised in adverse conditions, another one raised in good conditions, and 23 percent of their genes will be different. The fact of the matter is, environment matters.” In human education, the texts used and studied are a large part of the learning environment. Heckman’s studies support the notion that the texts used in human education should be as rich as possible, as early as practicable. It reasonably follows that the habit of study of great books – the richest of intellectual texts – should be developed as early as practicable, given the capacities of the students.

Heckman: “We do know roughly that the early years are very important and the later we wait, the harder it is [to enhance IQ]. We know there are a lot of differences genetically; there are a lot of differences that emerge. I’ll give you an example of gene-environment interaction. James Q. Wilson and Richard Herrnstein wrote a book called Crime and Human Nature about the determinants of crime. They said there is a genetic predisposition for crime, and there is! Have you heard about the MAOA gene? If you go to the State Prison of Georgia or any other prison you’re going to find an overabundance of what are called ‘MAOA genes.’ This gene is very predictive of violence, especially early onset violence. But it turns out — and this is an amazing finding, within the last several years — if you take two individuals with the same MAOA gene, one raised in a middle class environment, one raised in an environment with a tremendous amount of violence in the background and not much family support, it is only in the latter environment that the MAOA genes show any predictive power for criminality. In the middle class environment, it’s as if it never was there. That’s a powerful gene-environment interaction. And that’s just one gene! When you’re thinking about all of the genes we have and that 23 percent of all of them could be affected by these early environments.”

Genes are very important, but the environment in which genes are expressed is often your destiny. Heckman writes: “ I think [environment] is powerful. You can shut down the operation of a gene, because certain aspects of the gene will never manifest themselves, or certain negative aspects can be reinforced by it. The gene is still the same but it can be shut down, or it can be enhanced. We can change who we are. We can improve ourselves in various ways and we can give ourselves possibilities. What I’m thinking of is a sense of capabilities. It’s basically saying, give a child more possibilities to do whatever he or she wants to do with their life. So you give them more capacities: more capacities to solve math problems, more capacities to do music, etc.” [“It Pays to Invest in Early Education Says a Nobel Economist Who Boosts Kids IQ; Making Sense” – Feb. 22, 2013].

We believe a program of study of the world’s greatest literature covering the broad range of human intellectual endeavor and experience, is precisely the formula for enriching students’ learning environments, exposing them to more possibilities in life, and expanding their capabilities to pursue what is great, true and beautiful.

Adler too had great respect for the potentialities of the minds of teenagers, and did not want to see those formative years wasted, entailing the risk of losing the opportunity for liberal education altogether, which is so often the case. In a 1970 appearance on the TV show Firing Line, hosted by William F. Buckley, Jr, Adler had great respect for the potentialities of the minds of teenagers, and did not want to see those formative years wasted, entailing the risk of losing the opportunity for liberal education altogether, which is so often the case. In a 1970 appearance on the TV show Firing Line, hosted by William F. Buckley, Jr, Adler made the point that liberal education, the backbone of which is study of the Great Books (rather than a disorganized, smorgasbord of electives), should be completed by the end of secondary (high) school:

“I think the liberal arts degree is given four years too late. I would take American schooling and cut it down, and make it European in this sense: six years of elementary schooling; six years of secondary (lycee, gymnasium – high school); the collegiate degree (i.e., the Bachelor of Arts) coming at the end of that [i.e., at the conclusion of secondary/high school education – 12th grade in the US]…I might extend that by taking [into account] the differences in the population: I might have the very brightest twelve years [i.e., through 12th grade]; for the next level thirteen years; and the last, fourteen years, but not more than fourteen.”

That was Adler’s view in 1970, after spearheading the Great Books Movement, with Robert Hutchins, President of the University of Chicago, for half a century. For the next three decades until his death in 2001, Adler’s view did not change, rather it was repeatedly confirmed. In 1983 Adler wrote: “I have been conducting seminars for 60 years now, with students in high schools and colleges and with adults who have engaged in the reading and discussion of great books or who have been participants in the Aspen Executive Seminars. Long experience has convinced me that seminar teaching, on the Greek or Socratic model, not the German one, belongs not only in the colleges, but should be carried on also in high schools, where students have proved every bit as able to profit from seminars that I have conducted as have their college counterparts–have shown themselves even better participants in some ways.”

Three years later, in 1986 Alder again wrote: “Ideally, everyone should be both a generalist and a specialist–a generalist first at the level of basic schooling…Schooling from kindergarten through 12th grade would initiate the young in the process of acquiring general, liberal, and humanistic learning. The colleges and universities to which some of them then went would afford them opportunity for specialization in a field or fields that they elected to pursue.”

Seven years later, in 1990 Adler reaffirmed his consistent view that the Great Books should be studied in the high school years, “before age eighteen.” In a talk to the National Press Club on October 30th that same year, Alder made it clear that even 16-year- olds were quite able to complete a four-year program of study of the Great Books: “I wanted to have graduation from high school at age 16, not 18.”

In 1992 he wrote: “I even went so far as to suggest that the B.A. degree be given on graduation from high school, signifying the completion of the first stage of general education, and that undergraduate colleges becomes three-year institutions, giving the M.A., or some similar degree, for the completion of the specialized course, with a little general education retained as a carry-over from high school…If high school were completed at age sixteen instead of eighteen, then I proposed that, in the next two year , there should be compulsory nonschooling…as a result of two years of work experience, either in private or the public sector of the economy…they would be better students in college, because they would be more mature; and they would have a better sense of what they wanted to do with their lives.”

What about those who were unable to obtain a liberal education in high school? In 1992 Adler wrote that taking up the study of the great books after specialization in college was the next best alternative: “If future citizens were to be given that kind of education, which I thought prerequisite for the intelligent discharge of their civic duties, then that would have to be done before they went to college, or after they graduated from college, or better, at both times of their lives.”

This will doubtless raise the question in some minds as to whether, if one missed the opportunity in high school or homeschool, one ought to study the Great Books in a liberal arts or Great Books college program. The answer is certainly yes, to which the demand for Great Books college education, testified to by the growth and spread of Great Books colleges and Great Books college programs, such as at Columbia University, The University of Chicago, St. John’s College (Annapolis and Santa Fe), St. Mary’s College (Morgana, CA), Thomas Aquinas College (Santa Paula, CA), Gutenberg College (Salem, OR), Notre Dame’s Great Books Honors program, and at many other colleges and universities, gives eloquent testimony.

However, the vast majority of the 4,500 or so US colleges and universities do not offer a Great Books program, and while the list that do—at least in some fashion (from one or two courses up to four-year programs)—has grown to over 100 (see the Appendix for the list of these), that still represents only about 2% of the total number of colleges and universities in the US. Another 10% or so of tertiary institutions are liberal arts colleges, in varying degrees, but do not offer Great Books programs. Thus Adler’s advice above, to study the Great Books either before or after college, or both, remains relevant for the great majority of students, including his consistent advice to begin such study during the high school years, if possible, for the several reasons mentioned.

Three FAQ (discussed in order, following)

• Are the Great Books too difficult to be mastered by teenagers?

• Would the study of a small number of Great Books be sufficient for such an educational approach?

• If a student begins a Great Books program, what should the accompanying curriculum in other subjects look like?

1.) Are the Great Books too difficult to be mastered by teenagers?

Yes, they are too difficult to be mastered by young students. But that is beside the point—no high school, college or university student can “master,” plumb the depths nor exhaust the Great Books– that is the work of a lifetime. The error implicit in this objection is that schooling and education are synonymous, and that therefor mastering material–certainly one goal of education—must therefore take place at some point during formal education. Adler addressed this objection as follows:

“No one can become an educated person in school, even in the best of schools or with the most competent schooling. Schooling is only the first phase in the process of becoming educated, not the termination of it.” Education should not be identified with schooling. Rightly conceived, education is the process of a lifetime, and schooling, however extensive, is only the beginning of anyone’s education, to be completed, not by attendance at educational institutions in adult years, but rather by the continuation in learning through a wide variety of means during the whole of adult life. Hutchins put it well: “The college graduate is presented with a sheepskin to cover his intellectual nakedness.” Schooling can and should be terminated at a certain time, but education itself cannot be terminated short of the grave

If mastering the Great Books is beyond the ability of young students, what then is the point of studying them in high school or college? Stringfellow Barr, co-founder of the Great Books program at St. John’s College, Annapolis, responded to that question by saying that the students in the program were not expected to master the great books; few if any adults could be expected to do that. At St. John’s, he said, “the great books serve the purpose of a very large bone thrown to a young puppy. The puppy will wrestle with it, will probably not get much meat off it while agitating it, but will certainly sharpen its teeth in the process.”

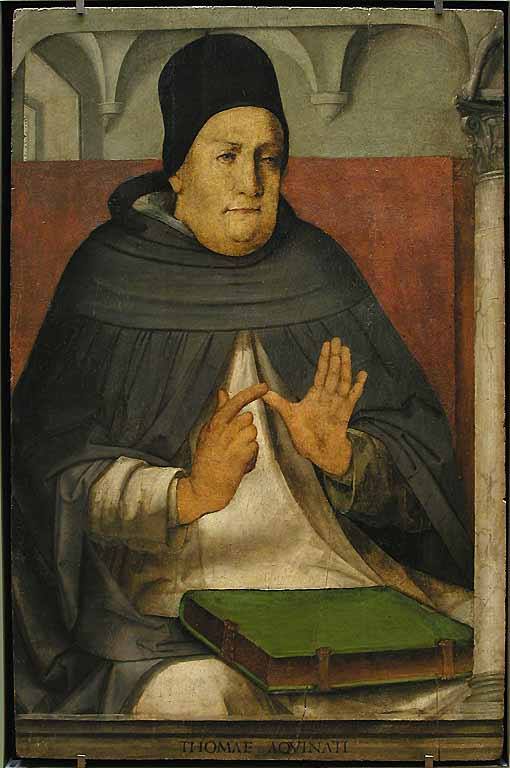

Jacques Maritain makes the same point with a like metaphor: “One cannot emphasize too much the educational role of the great books. Yet this role does not only consist in sharpening the intellectual power of the youth; they are not only like a large bone with which a puppy struggles so that his teeth may grow sharper. To bring the metaphor to completion, it should be added that this large bone is a marrow-bone, and that not only do the puppy’s teeth have to grow sharper, but his living substance also has to feed itself upon the valuable marrow. It is doubtless not a question for the young student of “mastering” the great books, but of discovering and being quickened and delighted by the truth and beauty they convey—and, if they convey errors too, of discerning and judging the latter, however awkward and imperfect this process may be at first. The intellect’s teeth are not really sharpened if they are not able to separate the true from the false.”

While mastery of the great books is beyond them, Adler noted that high school “students have proved every bit as able to profit from seminars that I have conducted as have their college counterparts–have shown themselves even better participants in some ways.” Again, “In 1933-34, Bob Hutchins and I undertook to read the great books with a selected group of juniors and seniors in the University [of Chicago] high school. Though younger than the students in our General Honors course in the college, the high school students did just as well; in fact, having had less schooling, they were somewhat less inhibited in discussion.”

It is the experience of the author, after conducting many great books seminars over the years and sharing notes with other Great Books moderators (or tutors, as they are often called), that high school-age students are generally more open and eager to consider the ideas and insights, and to accepting the occasional wisdom contained in the Great Books, while at the same time are not burdened with the radical skepticism that plagues our educational system which is inculcated in young minds by the radical skepticism and post-modern nihilism that plagues our higher educational system and which is inculcated in young minds by those schools and media. In other words, they generally still believe truth exists and can be known, and so generally make better students in Great Books programs than older students.

In 1986 Adler conducted five seminars in Chapel Hill, North Carolina for 20 students from Millbrook High School in nearby Raleigh. His experience there further confirmed his belief in the beneficial effects on high school-age students of studying the Great Books. The seminars were recorded and are still available. The Great Books texts discussed in the five sessions from Monday to Friday were: Plato’s Apology, in which Socrates defended himself at his trial in Athens; the first eight chapters of Book I of Aristotle’s Politics together with the first book of Rousseau’s The Social Contract; Machiavelli’s The Prince; the Declaration of Independence; and Sophocles’ Antigone. Adler described the experience:

“The seniors from Millbrook High School had never read any of these texts before and had never been in seminars in which texts they had read were discussed. Everyone agreed, both the students who participated in the seminars and the teachers who observed them, that the progress was remarkable—a progress that is visible to anyone who watches the five videotapes in succession.

Given this visible evidence of extraordinary progress in the growth of understanding, I asked my audiences to imagine what the results might be if, instead of just five days in their senior year of high school, these same students had had seminars once a week throughout all four years of high school; or, going further, I asked them if they could imagine that these same students had had seminars once a week from the third grade on to the twelfth. I told them they would fail because, I said, that result would be unimaginable. It would be beyond their fondest dreams.

One other insight emerged from the Millbrook seminars. The seminars did more for the students than increase their understanding of basic ideas and issues. They clearly improved the students’ skills in reading, speaking, and listening. Most of all they clearly had an extraordinary effect on their ability to think critically, a skill that cannot be taught in itself or in a vacuum, but only in the context of discussions that involved reading, speaking, and listening.

Van Langston, the principle of Millbrook High School, accompanied his students on the bus in their hour’s ride from Raleigh to Chapel Hill and back. I repeated something that he told me at the end of the week. He had been acquainted with these students for four years and, in his experience with them, they had never been found discussing anything but games, frivolities, making money, recreation of all sorts. But in the bus returning to Raleigh from Chapel Hill each afternoon after the seminar was over, they engaged in agitated discussion of ideas and issues with which they had been confronted in the seminars.”

One final observation on this question: despite his later intellectual accomplishments, Adler himself was a high school drop-out. At age fifteen he read the autobiography of John Stuart Mill, who though entirely unschooled (not uneducated) had read many of the great books in the Western tradition before the age of eleven. When he read Mill had read the Platonic dialogues by age five, Adler had to read them! There Alder discovered his lifelong hero, Socrates. Lacking a high school diploma, young Adler nevertheless managed to get into Columbia College where he began the study of the Great Books. This personal experience of what was possible for young intellects, even though unschooled as Mill was, or a high school drop-out as Adler was, convinced him never to underestimate the learning capacity of young minds, as his later experiences—some recounted above—confirmed, many times, over the next eight decades of his life.

2.) Would a small number of Great Books be sufficient, perhaps better, for such an educational approach?

What of the objection that a reading and discussion program introducing one book (or major excerpt) a week, 120 or so over four years, cannot serve as more than an introductory or survey course in the classics, which should be read much more carefully—only a few a year—and more in depth rather than for breadth?

Among those who promote the study of the Great Books there has been some debate regarding the ideal number of Great Books to be read in a year, or more, and the time which should be devoted to their study. As noted above, Dr. Adler and Jacques Maritain believed the four high school years should be largely devoted to the study of great books, and our extensive experience with four year programs over the last 15 years strongly supports that view.

Studying a handful of Great Books in one semester, or in two or even six semesters does not allow sufficient time to accomplish the purpose of acquainting the students with enough of the Great Books to give them a sense of their full range and scope. Of course there is nothing magical about a four year program, but besides offering the opportunity of at least acquainting the students with 120 or so of the Great Books and the great ideas contained therein, there is something quite practical about it as well: compulsory schooling in the US is widely set at 12 years and most, or at least many, students have learned the basic liberal arts by the completion of 8th grade, leaving 9th to 12th grades available for applying those learning arts to something – the best something being Great Books. We have found four years reasonably sufficient for that purpose.

In four years a Great Books program may be divided into what has become a more or less standard, chronological sequence of the ancient Greek, Roman, Medieval and Modern Great Books, each studied for an academic year of two semesters. Studying about 30 books from each roughly 400 year time-period, in chronological order, gives students a broad and substantial exposure to the intellectual life of each period, to the great ideas discussed in them, and to that portion of the Great Conversation—the ongoing intellectual dialogue of Western civilization contained in the Great Books—written in each period.

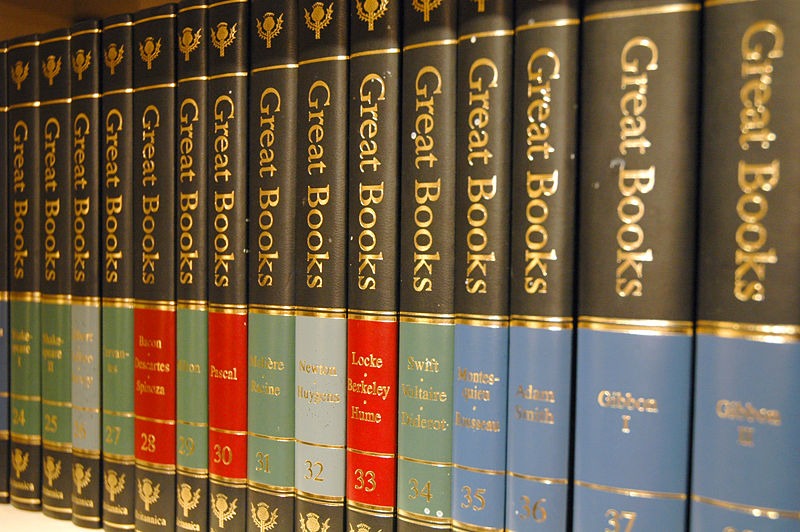

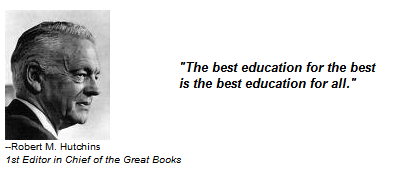

To reduce the number of books significantly would break the thread of the Great Conversation which requires—at its best—representative works connecting great books discussing the great ideas contained in them, without skipping any lengthy period of time in which they were further discussed and developed, from Homer to the present. As stated above, even four years is not sufficient time for an in depth study of the Great Books, but neither is the whole time of formal education sufficient–-that is the work of a lifetime. “The object of education is to prepare the young to educate themselves throughout their lives.” –Robert M. Hutchins

To reduce the number of books significantly would break the thread of the Great Conversation which requires—at its best—representative works connecting great books discussing the great ideas contained in them, without skipping any lengthy period of time in which they were further discussed and developed, from Homer to the present. As stated above, even four years is not sufficient time for an in depth study of the Great Books, but neither is the whole time of formal education sufficient–-that is the work of a lifetime. “The object of education is to prepare the young to educate themselves throughout their lives.” –Robert M. Hutchins

It may be objected that there are such gaps even when selecting 120 or so great books for a four year program, which is true. However, if each of the Great Books selected included the thoughts of the authors of the Great Books for a like number of years, each of the 120 books selected would only need to cover 23 years to total to the 2,750 or so years from Homer to the present. This is much too arithmetic and simple of an analysis solely to rely upon, for any purpose, to be sure. But the point remains that a four year program can at least acquaint students broadly, and chronologically, in the order of discovery, with virtually the whole range of the history of thought and intellectual activity in Western civilization, and the various fields and principal authors and great ideas included—oftentimes exposing them to whole areas of thought and knowledge about which they were previously unfamiliar.

It is a uniform experience in Great Books programs of significant length, that a number of students previously aiming at trades, business, engineering, or law, shift their interests to literature, philosophy, history, political science or other of the humanities. That is not the goal of great books programs, it is however an inevitable effect of broadening horizons and opening minds to new possibilities either not previously considered or insufficiently considered and undervalued in and by our educational system.

Too often schools educate to serve the narrow interests of for-profit enterprises eager for narrowly trained workers useful for short range purposes, who in a few short years are often left unemployed due to learning only a few limited skills made obsolete by the rapid pace of technological innovation. A broad, liberal education can give them skills and knowledge necessary to be able to adapt to rapid change and a wide variety of challenges.

“Education is not to reform students or amuse them or to make them expert technicians. It is to unsettle their minds, widen their horizons, inflame their intellects, teach them to think straight, if possible.” –Robert M. Hutchins

That being so, it is obvious a program could nevertheless attempt to cover too many books, even if the main purpose is simply familiarity and introduction. Maritain warned of this: “That is why the great books should not be too many in number, and their reading should be accompanied by enlightenment about their historical context and by courses on the subject matter.” This caveat was in the context of praising and agreeing with Adler’s promotion of the study of the Great Books a la’ Erskine’s approach at Columbia University, which involved the study of roughly one book per week. That one-book-a-week approach and approximate pace is used in most four-year Great Books programs. Of course one key reason is that, with some exceptions, it is possible, and very practicable, for high schoolers, and up, to read one book a week during the academic year. Decades of experience have proven this.

What about really difficult works, such as Aristotle’s? In every Great Books program, more difficult works, those that it would be too much to expect young students to read in a week, are either broken into two or more weeks of reading, or only important, major excerpts are read. Additionally, in most cases the most difficult works (usually philosophy or the natural sciences) fall into the Modern period, and so are read by students in the later or fourth year of the program (if a four year program), when they are much better readers, long experienced in reading books of all kinds.

Of course what this means over the four years of high school or undergraduate college is that approximately 120 great books or major excerpts are read during a typical four-year great books program. Shorter great books programs reduce the number accordingly.

When one gets beyond the rather generic title “Great Books” one can begin to see the advantages of Erskine’s and Adler’s approach of one book per week. It is difficult to reduce and prioritize the works in the various sets of great books (e.g., Britannica’s Great Books of the Western World includes 517 works) to 120 or so. Perusing a typical four-year Great Books Program reading list will give the reader some idea of the difficulty, and loss, in further reducing the list (to shorten it, should one leave out Homer, or Moses, Plato, Virgil, Augustine, Aquinas, Chaucer, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes, Darwin, Freud, Einstein, or the like ?). Is a student who has never read, perhaps never even heard of, such great works truly educated or prepared to become so? The compulsory high school years of education (or undergraduate education) typically last four years, hence the logic of using all four of them most wisely, studying the works of the wise, and not wasting them on mediocre, or worse, materials.

3.) If a student begins a Great Books program, what should the accompanying curriculum in other subjects look like?

The primary grades (usually k-8 in the US) are intended to instruct the students in the elements, or grammars, of the liberal arts (hence we refer to them as elementary or grammar schools)–the learning arts–so that they possess for themselves the tools of learning. We will discuss elsewhere what those tools are, but they include the arts of reading, writing, speaking, listening, and calculating, sometimes summed up as the 3 R’s (reading, writing and ‘rithmetic [or reckoning]). If that goal is accomplished reasonably well, that leaves the four traditional high school years (9th-12th grades) for applying those newly-learned liberal arts to gaining a liberal, generalist education by studying proper materials. The learning or liberal arts understood in the strict sense are only a part—the first part—of a liberal or generalist education.

A student who has learned only the liberal arts (think the 3 Rs) but has never applied them to excellent material for study (such as the Great Books), would know how to read, write, speak, listen and calculate, but neither what to write about nor why to do so. It’s more than semantics: the liberal or learning arts are just as necessary for vocational, professional or specialized learning today as they are for a generalist education–everyone in modern society needs to know how to read, write, speak, listen and calculate. The key difference is whether, before specialization occurs, they first have the opportunity to apply those arts to a broad range of material selected for the specific purpose of gaining a liberal education in the full, generalist sense of the term. If not, then they may have learned the liberal arts, in the strict sense, but are not liberally educated, at least not fully so. As Hutchins put it, “they will have escaped illiteracy without ever achieving true mental cultivation.”

Regarding the first twelve years of education Adler wrote: “All normal human beings should have the same basic schooling for twelve years.” “I think the curriculum for liberal studies should be completely fixed. There should be no electives at all. I do not think the student is in any position to make choices about what he should study. I do not think his interests make any difference. They are all human beings; they are all going to become citizens; they are all going to have lots of free time. I think electives–the choice of specialization–should come after the liberal arts degree.

To the criticism that a completely required curriculum imposes too much discipline and reduces freedom, Stringfellow Barr replied by reminding the critics that the undirected often suffers a worse fate than a loss of freedom. The ship that will not answer to the rudder, he remarked, must answer to the rock.

In another article we will examine the specific, fixed courses Adler and other reformers recommend to accompany Great Books courses. The reader may find interesting Adler’s suggestion regarding taking a break from formal education in the time after completion of liberal education and before specialization (so after high school in his ideal model):

“There should be a hiatus [from school] of at least two years–I would prefer four…[students] certainly cannot become mature as long as they remain in school; on the contrary, they suffer from prolonged adolescence. That is a pathological condition which can be prevented only by getting the young out of school as soon after the onset of puberty as possible.”

To summarize Dr. Adler’s views on the questions posed in this chapter: he strongly believed in beginning a four-year, liberal education including, as the most important and central part, weekly Great Books seminars, in secondary education, to be completed by age 18, which closely accords with Maritain’s view of conducting high school liberal education including the study of the Great Books in the four years from age 16 to 19. Both philosophers believe completion of such a secondary/high school, generalist education would merit the award of a Bachelor of Arts degree, freeing subsequent tertiary education at U.S. colleges and universities, and the time and treasure spent there, for specialization.

![Dr. Mortimer Adler [sitting] at his last Great Books Discussion Group, (2000 A.D.), with the initial online Great Books Program directors [standing, left to right] Steve Bertucci, Pat Carmack (the author), and Tom Orr](http://www.angelicum.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/pat.jpg)

Dr. Mortimer Adler [sitting] at his last Great Books Discussion Group,

(2000 A.D.), with the initial online Great Books Program directors

[standing, left to right] Steve Bertucci, Pat Carmack (the author), Tom Orr

The rapid expansion of dual enrollment high school/college courses, early college courses, and similar use of Advanced Placement, Advanced Standing, CLEP, IB, and ACE college credit recommendations, for which high school, homeschool, or independent students can earn college credits for completing courses and/or tests of college level content and rigor, confirm Alder’s and Maritain’s esteem for the learning capacity of teenage minds and what they can achieve with the best educational opportunities and materials. All of these hybrid courses also serve to reduce the financial burden of endlessly increasing college costs, as they are generally available for a fraction of the cost of regular college tuition, room and board.

Online Great Books Programs, since they are not limited by classroom size, enable potentially limitless numbers of students the opportunity to gain a broad, liberal education in the humanities through the study of the greatest books of Western civilization, while in high school or home school (and older as well), via distance education, for personal growth, and for college credit.

Copyright 2015 All Rights Reserved by Patrick S.J. Carmack, J.D.

Footnotes omitted

Dr. Mortimer J. Adler

In 1983, Dr. Adler, who had been a lifelong student of Plato, Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas (and a member of the American Catholic Philosophical Assiociation), formally converted to Christianity, specifically to the denomination of his wife, who was Episcopalian. Sixteen years later, in December, 1999 in San Mateo, California where he lived and shortly thereafter passed away (d. June 28th, 2001), he was formally received into the Catholic Church by His Excellency, Bishop Pierre DuMaine, of San Jose, CA, who was a long-time friend and admirer of Dr. Adler.

By Robert M. Hutchins

By Robert M. Hutchins

The tradition of the West is embodied in the Great Conversation that began in the dawn of history and that continues to the present day. Whatever the merits of other civilizations in other respects, no civilization is like that of the West in this respect. No other civilization can claim that its defining characteristic is a dialogue of this sort. No dialogue in any other civilization can compare with that of the West in the number of great works of the mind that have contributed to this dialogue. The goal toward which Western society moves is the Civilization of the Dialogue. The spirit of Western civilization is the spirit of inquiry. Its dominant element is the Logos. Nothing is to remain undiscussed. Everybody is to speak his mind. No proposition is to be left unexamined. The exchange of ideas is held to be the path to the realization of the potentialities of the race.

At a time when the West is most often represented by its friends as the source of that technology for which the whole world yearns and by its enemies as the fountainhead of selfishness and greed, it is worth remarking that, though both elements can be found in the great conversation, the Western ideal is not one or the other strand in the conversation, but the conversation itself. It would be and exaggeration to say that Western civilization means these books. The exaggeration would lie in the omission of the plastic arts and music, which have quite as important a part in Western civilization as the great productions included in this set. But to the extent to which books can present the idea of a civilization, the idea of Western civilization is here presented

These books are the means of understanding our society and ourselves. They contain the great ideas that dominate us without our knowing it. There is no comparable repository of our tradition. To put an end to the spirit of inquiry that has characterized the West it is not necessary to burn the books. All we have to do is to leave them unread for a few generations. On the other hand, the revival of interest in these books from time to time throughout history has provided the West with new drive and creativeness. Great Books have salvaged, preserved, and transmitted the tradition on many occasions similar to our own.

These books are the means of understanding our society and ourselves. They contain the great ideas that dominate us without our knowing it. There is no comparable repository of our tradition. To put an end to the spirit of inquiry that has characterized the West it is not necessary to burn the books. All we have to do is to leave them unread for a few generations. On the other hand, the revival of interest in these books from time to time throughout history has provided the West with new drive and creativeness. Great Books have salvaged, preserved, and transmitted the tradition on many occasions similar to our own.

The books contain not merely the tradition, but also the great exponents of the tradition. Their writings are models of the fine and liberal arts. They hold before us what Whitehead called “‘the habitual vision of greatness.” These books have endured because men in every era have been lifted beyond themselves by the inspiration of their example, Sir Richard Livingstone said: “We are tied down, all our days and for the greater part of our days, to the commonplace. That is where contact with great thinkers, great literature helps. In their company we are still in the ordinary world, but it is the ordinary world transfigured and seen through the eyes of wisdom and genius. And some of their vision becomes our own.”

Until very recently these books have been central in education in the West. They were the principal instrument of liberal education, the education that men acquired as an end in itself, for no other purpose than that it would help them to be men, to lead human lives, and better lives than they would otherwise be able to lead.

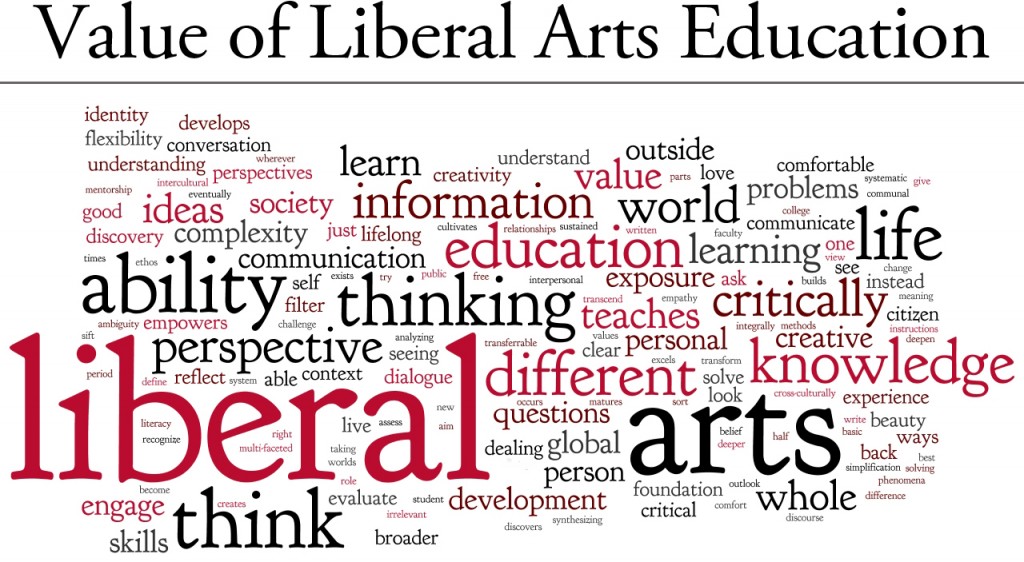

The aim of liberal education is human excellence, both private and public (for man is a political animal). Its object is the excellence of man as man and man as citizen. It regards man as an end, not as a means; and it regards the ends of life, and not the means to it. For this reason it is the education of free men. Other types of education or training treat men as means to some other end, or are at best concerned with the means of life, with earning a living, and not with its ends.

The substance of liberal education appears to consist in the recognition of basic problems, in knowledge of distinctions and interrelations in subject matter, and in the comprehension of ideas.

The substance of liberal education appears to consist in the recognition of basic problems, in knowledge of distinctions and interrelations in subject matter, and in the comprehension of ideas.

Liberal education seeks to clarify the basic problems and to understand the way in which one problem bears upon another. It strives for a grasp of the methods by which solutions can be reached and the formulation of standards for testing solutions proposed. The liberally educated man understands, for example, the relation between the problem of the immortality of the soul and the problem of the best form of government; he understands that the one problem cannot be solved by the same method as the other, and that the test that he will have to bring to bear upon solutions proposed differs from one problem to the other.

The liberally educated man understands, by understanding the distinctions and interrelations of the basic fields of subject matter, the differences and connections between poetry and history, science and philosophy, theoretical and practical science; he understands that the same methods cannot be applied in all these fields; he knows the methods appropriate to each.

The liberally educated man comprehends the ideas that are relevant to the basic problems and that operate in the basic fields of subject matter. He knows what is meant by soul. State, God, beauty, and by the other terms that are basic to the insights that these ideas, singly or in combination, provide concerning human experience.

The liberally educated man has a mind that can operate well in all fields. He may be a specialist in one field. But he can understand anything important that is said in any field and can see and use the light that it shed upon his own. The liberally educated man is at home in the world of ideas and in the world or practical affairs, too, because he understands the relation of the two. He may not be at home in the world of practical affairs in the sense of liking the life he finds about him; but he will be at home in that world in the sense that he understands it. He may even derive from his liberal education some conception of the difference between a bad world and a good one and some notion of the ways in which one might be turned onto the other.

The method of liberal education is the liberal arts, and the result of liberal education is discipline in those arts. The liberal artist learns to read, write, speak, listen, understand, and think. He learns to reckon, measure, and manipulate matter, quantity, and motion in order to predict, produce, and exchange. As we live in the tradition, whether we know it or not, so we are all liberal artists, whether we know it or not. We all practice the liberal arts, well or badly, all the time every day. As we should understand the tradition as well as we can in order to understand ourselves, so we should be as good liberal artists as we can in order to become as fully human as we can.

The method of liberal education is the liberal arts, and the result of liberal education is discipline in those arts. The liberal artist learns to read, write, speak, listen, understand, and think. He learns to reckon, measure, and manipulate matter, quantity, and motion in order to predict, produce, and exchange. As we live in the tradition, whether we know it or not, so we are all liberal artists, whether we know it or not. We all practice the liberal arts, well or badly, all the time every day. As we should understand the tradition as well as we can in order to understand ourselves, so we should be as good liberal artists as we can in order to become as fully human as we can.

The liberal arts are not merely indispensable; they are unavoidable, Nobody can decide for himself whether he is going to be a human being. The only question open to him is whether he will be an ignorant, undeveloped one or one who has sought to reach the highest point he is capable of attaining. The question, in short, is whether he will be a poor liberal artist or a good one.

The tradition of the West in education is the tradition of the liberal arts. Until very recently nobody took seriously the suggestion that there could be any other ideal. The educational ideas of John Locke, for example, which were directed to the preparation of the pupil to fit conveniently into the social and economic environment in which he found himself, made no impression on Locke’s contemporaries. And so it will be found that other voices raised in criticism of liberal education fell upon deaf ears until about a half-century ago.

This Western devotion to the liberal arts and liberal education must have been largely responsible for the emergence of democracy as an ideal. The democratic ideal is equal opportunity for full human development, and, since the liberal arts are the basic means of such development, devotion to democracy naturally results from devotion to them. On the other hand, if acquisition of the liberal arts is an intrinsic part of human dignity, then the democratic ideal demands that we should strive to see to it that all have the opportunity to attain to the fullest measure of the liberal arts that is possible to each.

This Western devotion to the liberal arts and liberal education must have been largely responsible for the emergence of democracy as an ideal. The democratic ideal is equal opportunity for full human development, and, since the liberal arts are the basic means of such development, devotion to democracy naturally results from devotion to them. On the other hand, if acquisition of the liberal arts is an intrinsic part of human dignity, then the democratic ideal demands that we should strive to see to it that all have the opportunity to attain to the fullest measure of the liberal arts that is possible to each.

The present crisis in the world has been precipitated by the vision of the range of practical and productive art offered by the West. All over the world men are on the move, expressing their determination to share in the technology in which the West has excelled. This movement is one of the most spectacular in history, and everybody is agreed upon one thing about it: we do not know how to deal with it. It would be tragic if in our preoccupation with the crisis we failed to hold up as a thing of value for all the world, even as that which might show us a way in which to deal with the crisis, our vision of the best that the West has to offer. That vision is the range of the liberal arts and liberal education. Our determination about the distribution of the fullest measure of these arts and this education will measure our loyalty to the best in our own past and our total service to the future of the world.

The great books were written by the greatest liberal artists. They exhibit the range of the liberal arts. The authors were also the greatest teachers. They taught one another. They taught all previous generations, up to a few years ago. The question is whether they can teach us.

“To be always seeking after the useful,” said Aristotle, “does not become free and exalted souls.”

In the spring of this year, education in our country was set into chaos. Teachers and administrators scrambled to find ways of delivering instruction in a remote setting. The fall rolled around, and the educational process had been revolutionized. With less class time for students, many teachers have pared down on their class material to “just the essentials.”

This, then, would be a good time to question what those essentials are. When it comes to the education of our children, what is most necessary? What is the real purpose and goal of education? It is always necessary to keep the goal of any activity in mind, especially an activity as important as education, but it is even more necessary in a time of upheaval.

Since I am a student of philosophy, I like to bother my students with deep questions that they don’t want to think about (some of these conversations are recorded in my book Philosophy Fridays). One of those questions, which I bring up a few times throughout the year, is this: why go to school? Students answer with the typical replies: to get good grades, to get into a good college, to get a good job, to make money, and so on. Basically, school is useful for getting along in life.

This is known as the utilitarian view of education, and they have been well-schooled in it. Students learn skills that will prepare them to fulfill some useful function in society. The job of a school is to fashion a gear for the machine of the economy.

One of the highlights of this year for me has been moderating Great Books discussions for the Angelicum Academy, and at the start of our first discussion (on Hesiod and Aeschylus, if you are interested), Steve Bertucci, the program’s director, offered a view of education that differs vastly from the technical view of our current society: the goal of education is to learn to love the things we ought to love. He cited Socrates.

Desmond Lee translates a passage of the Republic (Book III, 403c) this way: “The object of education is to teach us to love what is beautiful.” We ought to love what is truly beautiful, and we ought to love most what is most beautiful. Far from learning skills for work, education should be primarily about love and beauty.

Christopher Scott Sevier, in his book Aquinas and Beauty, comments, “What we love says a great deal about our character.” Education, then, is a formation of our character so that the beauty of what is beautiful can find a home in the beauty of a virtuous soul. Education is “training in virtue.” The development of right love is the development of the person as a whole. Well-ordered affection takes time and effort and ought to be the main thing in education.

Aristotle warned us, more than 2000 years ago, against the utilitarian view of education: “To be always seeking after the useful does not become free and exalted souls.” Who would not want the children of their world to become free and exalted in soul?

Again, Aristotle writes, “There is a sort of education in which parents should train their sons, not as being useful or necessary, but because it is liberal or noble.” The utilitarian view of education aims at developing useful humans. The educational view of Plato and Aristotle (and others) aims at developing excellent humans. Good skills are incidental to the human person. Being a good human is essential to the human person. As beings with free will, we participate in our own becoming. What we become depends on what we think, say and do.

One of the many quotes on my classroom wall reads: “One of the great problems of our time is that many are schooled, but few are educated.” That was written by St. Thomas More in the 16th century. I wonder what he would have to say about our schools now.

Epictetus said, “Only the educated are free.” For all our schooling, we are not free and exalted in soul. Only the virtuous are free. Only those who can love what they ought to love are free. Only those with well-ordered affection are free. Only those who can be pierced by what is truly beautiful are free, because Beauty is Truth, and “The truth will set you free.”

If education is being re-invented, it ought to be founded on solid principles. The essential thing about education is its purpose, and an education that loses its true purpose may turn out to be no education at all.

Matt D’Antuono is a physics teacher in New Jersey, where he lives with his wife and eight children. He holds bachelor’s degrees in physics and philosophy, a master’s degree in special education, and is working on a master’s degree in philosophy at Holy Apostles in Cromwell, Connecticut. He returned to the Catholic Church in 2008. He is the author of A Fool’s Errand: A Brief, Informal Introduction to Philosophy for Young Catholics, The Wiseguy and the Fool and Philosophy Fridays. On YouTube you can find him at DonecRequiescat and his family at MisterD418.

A Broader View

A Broader View

SUMMARY:

American Catholic families increasingly cannot afford Catholic higher education.

Private college, including room and board, cost an avg. of $1,187 per credit hour.

Great Books Program credits cost only $250 per hour for the first 48 hours of college credit;

The remaining Great Books Program college credits cost from as little as $250, depending upon the participating college selected.

The Great Books Program helps make Catholic higher education affordable.

Most Catholic parents hope to avoid sending their children to public, secular colleges with the attendant dangers to faith and morals so prevalent there. They hope to send their children to private four-year colleges for a sound, Catholic education. But that is increasingly unaffordable for families.

College tuition is typically based on a per-credit-hour basis, plus some minor fees (e.g., application fee). A credit hour is an “hour” (50 minutes) of class per week, for 14-16 weeks (a semester). The standard minimum number of hours for a bachelor’s degree in most US colleges and universities is completion of 120 hours, typically completed at the rate of 15 per semester, 30 per year for four years. Many foreign colleges and some US ones have 90 credit hour bachelor’s degrees, which typically require three years to complete. The cost-per-credit-hour therefore becomes central to calculating college tuition at most colleges, though a minority of colleges simply have a semester charge for a fixed curriculum.

College tuition is typically based on a per-credit-hour basis, plus some minor fees (e.g., application fee). A credit hour is an “hour” (50 minutes) of class per week, for 14-16 weeks (a semester). The standard minimum number of hours for a bachelor’s degree in most US colleges and universities is completion of 120 hours, typically completed at the rate of 15 per semester, 30 per year for four years. Many foreign colleges and some US ones have 90 credit hour bachelor’s degrees, which typically require three years to complete. The cost-per-credit-hour therefore becomes central to calculating college tuition at most colleges, though a minority of colleges simply have a semester charge for a fixed curriculum.

$ 142,544 – AVG. FOUR YEAR COLLEGE COSTS. 2009-2010 tuition and fee costs for private, four-year colleges increased on average 4.4% or $1,096 per year from the prior year to a whopping $26,273 per year (up 47% since 2002 when it was $18,596) or over $105,092 for four years; at the same time average college room and board costs climbed 4.2% or $377 per year to $ 9,363. That totals to an average of over $35,636 per year or $142,544 for a four-year degree (Ivy League colleges hover about $50,000 per year – $200,00 for four years

$ 1,187 PER CREDIT HOUR. Calculating the same average on a per hour basis, using the standard minimum of 120 hours for a bachelor’s degree, with room and board added in, the total cost is $1,187 per credit hour ($1,666 for the higher end colleges).

$ 250 PER CREDIT HOUR IN Great Books Program. The Great Books Program cost per credit hour is $250 for the first 48 hours ($12,000 total) of the program. The remaining hours vary from $250 (online courses) up to $600 (c. $912 including room and board, at Benedictine College).

Great Books Program BACHELOR’S DEGREES FROM $28,088. Eight bachelor’s degrees in the Great Books Program can be obtained for under $32,000.[iv] Another 31 Great Books Program bachelor’s degrees may be completed at residential colleges for a range from $28,088 (Campion Australia, including tuition, fees, room and board[v]), to $93,722 (Benedictine College, including tuition, fees, room and board) [iii] utilizing three annual 5% reenrollment discounts with the Angelicum Great Books Program), and absent any scholarships.

TEXTBOOKS REACH $1,000 PER YEAR. Add another $4,000 to tuition and fees at most colleges since the typical college student also pays another $1,000 per year on textbooks.[vi] Here are some pricey examples:

Acta Philosophorum The First Journal of Philosophy: $1,450

Encyclopedia of International Media and Communications: $1,215

Management Science An Anthology: $850

History of Early Film: $740

Biostatistical Genetics and Genetic Epidemiology: $665

Companion Encyclopedia of Psychology: $600

Feminism and Politics: $600

Concepts and Design of Chemical Reactors: $593

Advanced Semiconductor and Organic Nano-Techniques: $570

Ethics in Business and Economics: $550

Great Books Program BOOKS ARE UNDER $300 PER YEAR. By contrast, the Ignatius Critical Edition books used in the Great Books Program Angelicum Great Books Program cost approximately $11-13 each or roughly $300 per year. Our Great Books Study Guides are presently included in the price of the tuition. Since Ignatius does not have all of the books used in their Critical Editions yet, the current cost is under $300 per year (in fact, 80% of the four-years of readings are contained in Britannica’s Great Books of the Western World, a set which can be obtained new for $989 or used for much less).

CAN THE AVERAGE AMERICAN AFFORD PRIVATE COLLEGE ANY LONGER?

While college costs have continued to climb through the roof, average hourly earnings of Americans ($18.98 per hour) have declined in purchasing power to about ½ what they were in the 1970s, after adjusting for inflation. From January 2007 to 2009, 5.1 million jobs were lost; 13.7 million people were out of work and 32.2 million people were on welfare (food stamps). Many retirement plans are all but worthless. $9.7 trillion was spent on bank bailouts for a very few of the largest banks. An astonishing number of homes – 19 million – stand vacant. U.S. debt is approximately $12.3 trillion + $6.3 trillion Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac debt assumed by the US government = $ 18.6 trillion dollars. This vast sum does not include the federal government’s un-funded contingent liabilities such as Social Security/Medicare/Medicaid estimated at $107 trillion. State and local governments owe another $2.4 trillion. All of this will, of course, have to be paid on the backs of the already overburdened US taxpayer. The American middle class is now an endangered species.

While college costs have continued to climb through the roof, average hourly earnings of Americans ($18.98 per hour) have declined in purchasing power to about ½ what they were in the 1970s, after adjusting for inflation. From January 2007 to 2009, 5.1 million jobs were lost; 13.7 million people were out of work and 32.2 million people were on welfare (food stamps). Many retirement plans are all but worthless. $9.7 trillion was spent on bank bailouts for a very few of the largest banks. An astonishing number of homes – 19 million – stand vacant. U.S. debt is approximately $12.3 trillion + $6.3 trillion Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac debt assumed by the US government = $ 18.6 trillion dollars. This vast sum does not include the federal government’s un-funded contingent liabilities such as Social Security/Medicare/Medicaid estimated at $107 trillion. State and local governments owe another $2.4 trillion. All of this will, of course, have to be paid on the backs of the already overburdened US taxpayer. The American middle class is now an endangered species.

During the 1970s it was possible for American college students to pay their own tuition by working part time, without student loans or any help from their parents. Besides paying their own tuition, many students in the 1970s could also afford their own car and apartment. Today, college students have to get deeply into debt and have their parents help pay their tuition; students can barely afford to pay for food on their own.

One result is that parents and students increasing hope for scholarships, grants and especially student loans to make that more affordable. Beside these being uncertain and hence difficult to use in planning, there is a serious downside to student loans – sometimes crushing debt.

Consumer debt in the US stands at nearly $2.5 trillion dollars – and based on the latest Census statistics, that works out to be nearly $8,100 in debt for every man, woman and child that lives here in the US. We’re talking about consumer credit – which does not include debt secured by real estate. 36% is credit card debt (credit card delinquencies were at the third highest level on record);[vii] 64% is derived from loans that are not revolving in nature. This type of debt would include car loans and student loans. So if you’re thinking that number has mortgage debt in it, it doesn’t. The typical homeowner spends around 17% of their disposable income just to own their homes and cars. Renters outpace homeowners by over 8% and spend nearly 25% of their income on these same types of debts. Nearly one in every 35 households in the United States filed for bankruptcy in 2007 alone.

The Project on Student Debt, a research and advocacy organization in Oakland, Calif., used federal data to estimate that 206,000 people graduated from college with more than $40,000 in student loan debt – that’s a ninefold increase over the number of people in 1996, using 2008 dollars. Furthermore, on top of student loans most students have credit card debt they amassed from paying living expenses – $3,200 on average.

One survey of college graduates revealed an overwhelming number of respondents that were sidetracked from graduate or post-graduate study due primarily to existing student loan debt.[viii] Does this mean that if we were not faced with the mountain of student loan bills that we would be a more well-educated society? Of course, with many more well-educated Catholics.

The university and college tuition loan-finance system can now fairly be described as a continuous debt-generating apparatus. Students enter into college or university under the premise that once they receive their degree they will find high-paying jobs, enabling them not only to pay back their tuition debt along with other fees but be able, at the same time, to live a comfortable existence. Most recent graduates will tell you that nothing could be further from the truth.

Many entry-level wages for formerly “high-paying,” post-graduate positions were slashed – if those jobs did not disappear altogether. After their graduation, and with the onset of severe recession, more and more students have found themselves having to accept low-paying jobs in places like coffee shops or the retail industry just to cover their daily expenses.

For example, Cortney Munna, a 26-year-old graduate of New York University, has nearly $100,000 in student loan debt from her four years in college. Like many middle-class families, Cortney and her mother began the college selection process with a grim determination. They would do whatever they could to get Cortney into the best possible college, and they maintained a blind faith that the investment would be worth it.

Today, however, Ms. Munna, a 26-year-old graduate of New York University has nearly $100,000 in student loan debt from her four years in college, and affording the full monthly payments would be a struggle. Universities like N.Y.U. enrolled students without asking many questions about whether they could afford a $50,000 annual tuition bill. Then the colleges introduced the students to lenders who underwrote big loans without any idea of what the students might earn someday — just like the mortgage lenders who didn’t ask borrowers to verify their incomes.

Meanwhile Ms. Munna does not want to walk away from her loans in the same way many mortgage holders are. It would be difficult in any event because federal bankruptcy law makes it nearly impossible to discharge student loan debt. It is utterly depressing that there are so many people like her facing decades of payments, limited capacity to buy a home and a debt burden that can repel potential spouses.

Meanwhile Ms. Munna does not want to walk away from her loans in the same way many mortgage holders are. It would be difficult in any event because federal bankruptcy law makes it nearly impossible to discharge student loan debt. It is utterly depressing that there are so many people like her facing decades of payments, limited capacity to buy a home and a debt burden that can repel potential spouses.

How could her mother have let her run up that debt? “All I could see was college, and a good college and how proud I was of her,” her mother said. “All we needed to do was get this education and get the good job. This is the thing that eats away at me, the naïveté on my part.”

Cortney recently received a raise and now makes $22 an hour working for a photographer. It’s the highest salary she’s earned since graduating with an interdisciplinary degree in religious and women’s studies. After taxes, she takes home about $2,300 a month. Rent runs $750, and the full monthly payments on her student loans would be about $700.

She may finally be earning enough to barely scrape by while still making the payments for the first time since she graduated, at least until interest rates rise and the payments on her loans with variable rates spiral up. “I don’t want to spend the rest of my life slaving away to pay for an education I got for four years and would happily give it back,” she said. “It feels wrong to me.” [ix]

WILL THE OBAMA STUDENT LOAN REFORMS MAKE A DIFFERENCE?

In July, 2010 the US Government will take over a majority of issued student loans stemming from private banks and corporate-loan companies. Newly signed loans will have a capped 3.4 percent interest rate. The loans that already exist will not be affected by this cap, which means millions of students will still have to pay back their current loans with interest rates that can easily reach 10 percent or more. New repayment terms will come into existence for loans signed only after 2014. The current repayment cap of 15 percent of disposable income will be lowered to 10 percent. Furthermore, the government can forgive some borrowers’ debts after 20 years whereas now lenders can forgive student-loan debt only after 25 years. Public servants, i.e., nurses, soldiers, and teachers, could see more relief. Their debt can be forgiven after only 10 years, and they can get assistance of up to $4,000 for tuition. In addition, a portion of their loans can be forgiven if they make less than $65,000 per annum.

In July, 2010 the US Government will take over a majority of issued student loans stemming from private banks and corporate-loan companies. Newly signed loans will have a capped 3.4 percent interest rate. The loans that already exist will not be affected by this cap, which means millions of students will still have to pay back their current loans with interest rates that can easily reach 10 percent or more. New repayment terms will come into existence for loans signed only after 2014. The current repayment cap of 15 percent of disposable income will be lowered to 10 percent. Furthermore, the government can forgive some borrowers’ debts after 20 years whereas now lenders can forgive student-loan debt only after 25 years. Public servants, i.e., nurses, soldiers, and teachers, could see more relief. Their debt can be forgiven after only 10 years, and they can get assistance of up to $4,000 for tuition. In addition, a portion of their loans can be forgiven if they make less than $65,000 per annum.

Another aspect of the student-loan reform is the increasing of Pell Grants for lower-income students. As part of last year’s stimulus package, they were raised, but they would be lowered again once the stimulus money ran out. The amount of Pell Grants is slated to increase approximately $400 to $5,975 by 2017, correlated to fluctuations in the indices of consumer prices.

These changes are very vague and do not really address the central problems most students find themselves in. The estimation of the Consumer Price Index in 2017, for example, is an example of one of the vague features of the bill. Moreover, millions of students remain saddled with incredible amounts of debt. Most of the measures contained in the bill do not consider general inflation, and none of them considers tuition inflation.